1. Post-Covid Planning

As thoughts now turn to getting back (or moving forward) to some form of ‘future normal’, and our cultural institutions plan their re-openings and restarting their operations, Counterculture’s partners are busy helping our clients in the sector readjust to a new reality. Our Senior Partner, Stephen Escritt, has already developed a Post Covid Thinking & Planning tool, which is available on our website here. This helps cultural organisations map their way to the ‘next normal’, and considers the factors to be incorporated into the journey.

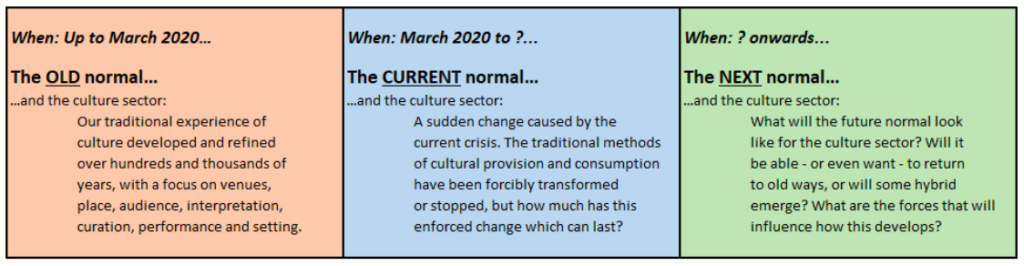

It is clear that the cultural sector is going to be much changed by this period. Although everyone is experiencing the same basic revolution, the speed and intensity of this transformation clearly varies from sector to sector. At a basic level, what we are all seeing is the following:

However, what isn’t clear yet is the degree of difference that this next stage will present, enforce upon, and be actively embraced by, the cultural sector compared to other sectors of society, as well as how long it will take to transition to it. Taken as a whole, the fear is that the cultural sector will be one of the hardest hit; museums, theatres and venues always seem to be at or near the bottom of the lists on websites and in newspapers discussing things slowly restarting, but that assumption – and the challenge within it – deserves some analysis.

2. Impact on the cultural sector

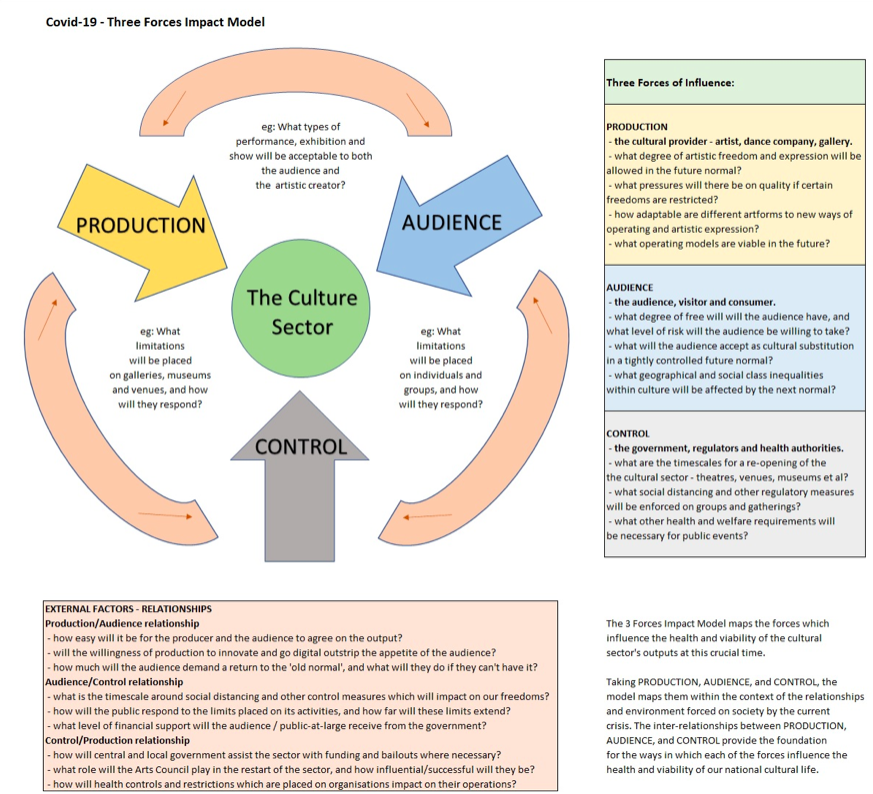

The following model looks at how three forces affect the cultural sector and its outputs at this time:

The cultural sector is of course not a homogenous entity, and can be broken down into different parts, different artforms, each of which will be impacted in different ways and intensity by this crisis. Some sections of the cultural sector will find adjusting more difficult than others. In order to test this, we’ve taken the Arts Council’s breakdown of artforms as the starting point for this analysis:

- Collections

- Combined Arts

- Dance

- Literature

- Museums

- Music

- Theatre

- Visual Arts

For some of these, the current crisis has simply accelerated trends which were already in motion. The approach to collections, for example, was increasingly about digital access and a significant change in the way collections are displayed and accessed, as exemplified by the V&A’s new Collections Research Centre in East London due to open in 2023. This trend of making collections more accessible by opening up and creating access to the collections in their storage environment is being repeated across Europe (for example the Depot Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam). This current crisis is unlikely to change this direction of travel; it may even make it a more compelling proposition, as much of the offer is about private access to collections rather than via mass galleries of visitors. New approaches to collections are in many ways very friendly to social distancing, with a re-emphasis on protection, cleanliness and conservation.

For other cultural artforms, the story is different. Breaking the music scene down into a number of sub-groups is useful because they’ve each been affected in quite different ways and intensities. The Classical Music scene struggles more than most – its audience is generally older and less tech-savvy, and while orchestras have developed online programmes, they tend to be archive performances, rather than new product. Where this is done well – such as the Berlin Philharmonic’s Digital Concert Hall – it is impressive in scope, choice and experience, but it also cannot eventually hide its limitations. There are some exceptions – the BBC Lockdown Orchestra is a good example – but these tend to be outreach and ancillary to the main product. The Classical Music scene’s experience in this crisis is a good example of fast-tracking the development of Learning and Community aspects of their programme, but in the ‘next normal’ are these aspects going to replace concerts and recordings?

The full impact of social distancing is as yet unknown, but where orchestras and opera companies rely so heavily on capacity audiences (the Royal Opera House breaks even at 95% capacity according to its CEO, Alex Beard), it isn’t difficult to see the troubles already being faced. The ROH is already planning a return involving the orchestra spread out into the Stalls, but this – and the inability to sell every adjacent seat that is left – isn’t sustainable.

Other live music is similarly struggling – the summer festival season is cancelled, and the significant number of businesses who rely on this activity and income are being decimated. Many small venues, whether core funded by the likes of the Arts Council or not, are likely to close – it might be some time before we get to experience a gig in a jam-packed hall or room. Even if this was allowed soon, who would want to do it? Of course the situation can change quickly; and this is reliant not only on science – the availability of a vaccine, and antibody test for example; but also on confidence and risk – will the yearning to see a band at Café Oto, Islington Town Hall or the Leeds Brudenell Social Club override the (possibly decreasing) risk involved?

Some venues and artists have put their shows online, but in doing so they are losing control of the quality of their product, and whilst the live experience-starved audience may lap it up as a temporary solution, it isn’t an experience different enough from just selecting that artist on Spotify to be sustainable; if the artist and venue succeed in making it truly special and unique, then may be this situation could change. The situation is the same with streamed and televised theatre and opera. There has been much noise around the NT Live programme – the One Man, Two Guvnors production in particular seemed to hit the sweet spot, and also resulted in a very significant level of donations to the National Theatre that evening. But, again, this isn’t sustainable – it wasn’t a substitute for sitting in the theatre, it felt like a temporary solution, it was no different from finding an archive performance online or even on DVD (!), and the whole experience, including the level of donations, reflected an audience saying we’ll do this for now, but not for too long. The NT Live programme also isn’t new – far from it – and just highlights the fact that this crisis is accelerating trends which were already happening; in most cases they aren’t solutions made in response to Covid-19, they just happen to be digital initiatives which were already in motion, and are therefore easier to appropriate.

Theatre, like music, will struggle with the demands of social distancing – the rescheduling of sold-out runs involving musical stars and actors with commitments elsewhere. For a scene where prices are notoriously high, it can only be expected that this situation will get worse, thus reinforcing the sense of elitism that accompanies the most expensive productions. There is a significant risk that the cost – in price and risk – will significantly worsen the inequalities, access to, and availability of theatre and the performing arts across the UK – with significant geographic variations, and ever-reducing opportunities for the less advantaged in society. The ‘them & us’ of culture is unfortunately only worsened by this period, and the London hegemony won’t be reduced any time soon.

For some in the visual arts, this period has been another opportunity – the contemporary scene is more used to change and technical innovation; and perhaps contemporary institutions and audiences are better suited to the forces of reinvention and embracing news ways of expression. This isn’t to say it has been easy, but some galleries, both large and small, have used the challenge of this period to offer something new. Examples include the X Museum in Beijing and M+ in Hong Kong (both of which have used the opportunities of capital projects to refine their digital offerings), and galleries such as David Zwirner (where AV content has been transformed) and the online version of The Line – London’s public art walk. Many online exhibitions, such as the Jim Dine at Alan Cristea, have been presented and framed in a new and visually stunning manner; and they somehow seem more primary product and less added-value than the online gig or the archive performance. Perhaps the control over quality is key here – it is much easier to ensure your online exhibition looks good to the remote viewer than it is to influence the sound quality for the remote listener. If these innovations, and a re-opening of the physical visual arts arena, are to persevere in the ‘next normal’ they will need to be aided by what is permissible. Too many restrictions will curtail innovation, but conversely may also provide a cause for the visual arts to rally against. For certain physical installations, it is hard to imagine us re-entering an environment where such sensitive and sensory elements such as Tania Bruguera’s 2018 Turbine Hall work can flourish.

Whilst some museums in Europe have announced their plans to reopen – Germany for example, is ahead of the game here, with some museums fully open already, albeit with significant security and social distancing restrictions – museums in the UK are waiting, listening, and planning. If the pattern in Germany is repeated here, we may find the smaller museums opening first, less constrained by the sizes of their estates, and less reliant on a degree of central government compliance. For the bigger ones, the challenge is immense, on many levels – whole programmes have been disrupted, vast estates need to be transformed to be socially distant-friendly, and thousands of staff need to be returned from furlough and trained. The programme challenge is a fascinating one; what will happen to scheduled blockbuster shows; the Hockney at the National Portrait Gallery for example had barely opened when the crisis hit, and it had to shut?

But museums and galleries also have an opportunity – whilst footfall is critical to them, it is not all concentrated in one concert hall or venue. They must make the most of this advantage to creatively choregraph the visitor journey, utilising as many innovative and technical tricks as they can to aid flow. With likely reduced building capacities, the museums may find themselves in an unusual situation which is counter-intuitive to their previous aims – rather than wanting visitors to extend their stay, they may want (and be encouraging) them to leave instead, except whilst in the shop of course.

All of this will be helped by an emergence into a post-Covid world which is sensible and sympathetic to an audience’s desire for cultural experience, as well as their acceptance of risk. The South Korea model, with temperature testing at the door, seems to be one way to go in the short-term, and not surprisingly is a way favoured by many major venues and performing arts organisations. This would assume a minimal level of control, letting people take the risk they are comfortable to take; but our UK experience so far doesn’t initially suggest that UK society will either want – or be let – to go down this route. However, we shouldn’t impose strict restrictions on arts businesses struggling to cope, and for whom an elongated period of social distancing and the like could be the final nail in their coffin.

Whilst we wait for the dust to settle in this chapter amid too many future unknowns, one question persists – will cultural life ever return to anything that closely resembles the old normal?

3. Operational Readiness – Post-Covid Transition

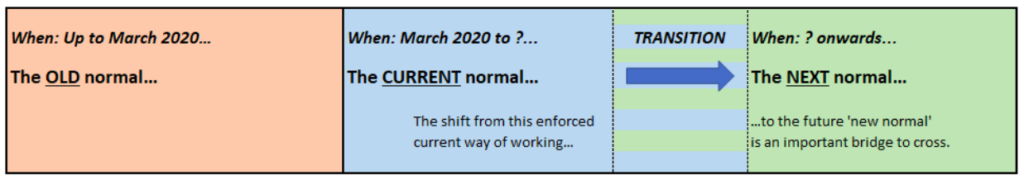

The transition between the different stages (the different ‘normals’) is another area of focus for Counterculture. Although the transition from ‘old normal’ to ‘current normal’ was a sudden one, and one for which everyone was understandably ill-prepared, we have relatively more time to think about the next change – between the current and next normals – and it is a crucial change to get right and manage properly:

But how long will this transition take? What factors across all three forces are influencing this process? And how does a cultural organisation manage this remobilisation?

The government’s short-term plan, delivered by the Prime Minister to the nation on the evening of Sunday 10th May gives us a few clues as to a possible timetable for this transition stage, but this is just one of the forces of influence. Also, crucially, there is no mention of culture. We are still in the realms of guessing, and planning for the moment, whenever that will be. Applying some project management thinking to the culture sector’s remobilisation plans will be useful at this stage, as it will allow us to set down some basic principles and areas of focus whilst we await further developments and guidance centrally. These areas of focus can also then be shifted easily to reflect changes along the road to a full reopening, or full return to some semblance of how things were before.

The duration of the transition period is therefore influenced firstly by the controls on society, but following this news closely are the cultural organisations planning their response and new offer, and the audience waiting for the green light to be let loose. For the cultural organisation, the remobilisation planning must be paying a close attention to the messages coming from government and Public Health England, but also to what the audience is saying it wants. This remobilisation planning stage is therefore critical, as it shouldn’t be isolated from the forces of control and audience, and it should be ensuring that the organisation is operationally fit and prepared for delivery.

Operational considerations for cultural organisations include:

- Resources – what level of resources are needed to deliver the remobilisation?

- Staffing – bringing staff back, re-energising and re-motivating them;

- Training – invest in your staff and train them in the requirements of the ‘next normal’;

- Estates – what requirements are necessary to ensure the premises is compliant?

As well as a planning tool for a post-Covid world, at Counterculture we also have the tools for the delivery of this new reality. We have been working with cultural organisations for many years on major projects and a programme of Operational Readiness©. This bespoke programme has been developed by Counterculture when working on major capital projects such as the new Tate Modern and in particular on projects at the V&A (both in London and Dundee). It looks at energising and coordinating the different forces required to open a new museum or integrate a significant new extension or refurbishment. As our cultural institutions plan their reboot from this current crisis, there is much they can learn from this programme – are they operationally ready for reopening; have they considered all of the organisational and operational implications of re-opening their offer to a new world? Are they in a fit and proper state to re-open; are they making the necessary adjustments to their operations – taking into account new regulations – in this brave new world?

We have developed a Transition Plan to help organisations with this remobilisation. To download a PDF version of our tool, please click here.

If you would like an excel version of the framework to adapt for your own use, please email Chris Potts – chris@counterculturellp.com

This planning tool can be tailored to the different requirements of organisations, allowing them to map the areas of work and tasks which need to be addressed throughout the transition period. It can be used in multiple and flexible ways; including as a way of monitoring the organisation’s progress across each work phase, as a checklist of tasks across the period, and as a way to structure the risk management and scenario planning which is crucial to the development of a future operating model for the ‘next normal’.

It is important that organisations:

- Commit the necessary resources to planning and internal management;

- Treat it as a programme, and have a dedicated resource coordinating and aligning all activities;

- Think creatively about how activities are delivered, how economies of scale and core competencies can be best utilised, and how partnerships can make less create more;

- Radically assess which activities to do more of, less of, to start doing or to cease;

- Develop a communications strategy internally and externally that is aligned and focused;

- Allow the programme to breathe – we are living in a fast-changing environment, so demonstrating agility and flexibility is key to success; and…

- Don’t try and do too much at once!

4. How can Counterculture help?

Counterculture can help your organisation build a bespoke transition plan if you need help with your remobilisation. Whether you want help across the entirety of your organisation, or just concentrated in one area, department or business unit, we can scale a solution that fits for you and your needs at this time.

So, whether your need is related to POST-COVID PLANNING or the delivery of the POST-COVID TRANSITION, we can help you to develop your thinking, your new operating model, and the all-important transition and remobilisation for the ‘next normal’.

If you wish to speak to one of us at Counterculture about preparing for your ‘next normal’ and supporting you through the delivery of this process, please do get in touch.

Photo by YIFEI CHEN on Unsplash

Chris is a capital project and strategic operations expert in the arts and charity sectors. He specialises in developing, structuring and leading capital projects and managing the maintenance and assets of public buildings – ensuring organisational efficiency and optimum use of complex and multi-functional spaces. His work encompasses capital projects, organisational development, licensing, accounting, governance, […]

Read Chris’s profile